Science, Literacy and ELA Standards: Strategies for the K-5 Classroom

“You can’t do science instruction effectively without literacy skills instruction. In fact, students should be writing, reading, and communicating like scientists constantly,” says Andrew Miller, an instructional coach at Shanghai American School.

Looking at the standards, the relationship between English language arts (ELA), science and math is clear. In this Venn diagram published by Stanford University, one can see the interconnection of skills necessary for students to succeed in these fields.

To be ready for college, career and the increasingly complex choices required in everyday life, students need to develop critical-thinking skills and the ability to closely and attentively read texts. According to the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) website, students should be able to “read stories and literature, as well as more complex texts that provide facts and background knowledge in areas such as science and social studies.” And they should “be challenged and asked questions that push them to refer back to what they’ve read.” In this way, the CCSS stress problem-solving and analytical skills. These skills are developed most fully in grades 6-12, but important foundations are laid in elementary school.

Ideas for Building Science Literacy in Elementary School

Miller suggests that teachers reflect on this question as they design lessons, units and other instructional activities: “How do I help my students read, write and speak like scientists?” And he offers these ideas for materials to incorporate: “Consider texts that scientists interact with regularly like magazines, website, and reports. Consider written products that scientists do, such as lab reports, websites, and even funding requests. Consider presentation products such as group presentations, demonstrations, and podcasts.”

These texts and products can be used as a foundation for a number of lessons across the curriculum. “Younger students might create a science guide to plants that is more pictorial in nature or even a video tour of a garden to build speaking and listening skills,” Miller says. “Upper elementary students might create a website or written blog about a science topic to work on writing readings.”

Creating Authentic Science Tasks

To both reinforce science content and build literacy skills, students need to engage with a real-world problem. Miller provides this example of an assignment: “In a mouse trap project a teacher did with third-grade students at my school, she launched with a video of mice escaping mazes and a demonstration of different mouse traps, and then she presented students with the challenge of creating effective mouse traps. For products and assessments, students recorded video reflections of their designs and set goals. They created a blueprint and rationale for their final design, and along the way they read a variety of articles and directions on effective traps and content related to science,” he says.

“The key here is authenticity, and thinking about authentic science tasks students can do. As tasks become more relevant and real, the literacy tasks do too, and the students’ work mimics what adults in the science field do every day.”

Creating Text-Dependent Questions

Miller recommends another key strategy for supporting K-5 readers in developing their literacy skills: prompting them with questions that drive them to return to the text. In his article on Edutopia, he acknowledges that developing these questions can be difficult, but fortunately there are ample resources for getting students to return to the text.

He says, “You can assign students content area reading, and then have them write about this content to show their learning, all while targeting specific literacy objectives. In addition, the Literacy Design Collaborative specializes in modules with these types of questions. You can use their templates to create your own modules, or use many of their already existing modules that have been juried and peer reviewed. The best part is that the templates and tasks have the Common Core hardwired into them, so you don't need to worry about figuring which standards you are addressing.”

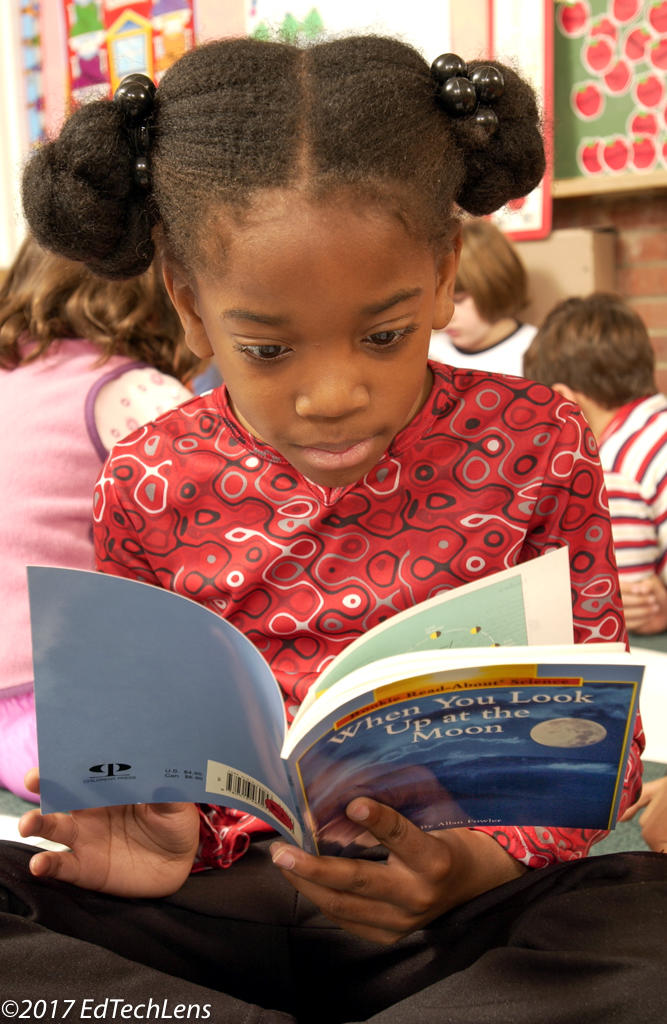

Reading in the Science Content Areas

With educators strapped for time in their efforts to meet the requirements for CCSS math and ELA standards, in some instances, science and social studies have been crowded out. Fortunately, there are time-efficient ways to bring these subjects in via books. Doing so also dovetails nicely with the CCSS ELA requirement that students read a fairly high percentage of nonfiction. Science books help meet that requirement.

But assigning reading and writing alone isn’t enough. This helpful page in the Minnesota STEM Teacher Center summarizes the research that shows students need to see examples and demonstrations of how scientists discover and communicate their findings. They need instruction in and opportunities to practice and model skills like thinking aloud, asking questions and making claims, collecting pertinent information and conducting research, illustrating what they’re learning and presenting findings.

It goes on to say, “through interactions with science, students develop interest, purpose, and excitement as they go to text to support their interest in the scientific phenomenon. Science builds engagement; engaged readers learn more.”

About Andrew Miller: As a classroom teacher, instructional coach and online teacher, Miller has taught in many settings, from a comprehensive high school, to a 6th-12th grade Project Based Learning and STEM school. He has taught subjects from English and Social Studies to Technology and Game design through implementing small-scale to extensive integrated projects. Currently, Andrew is an Instructional Coach at the Shanghai American School in China with a heavy focus on Understanding By Design®, Assessment and Project Based Learning. He also serves on the faculty for ASCD (formerly the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development). He has supported educators in the United States, Canada, Mexico, Kuwait, India, China, Australia, and the Dominican Republic. Andrew is also the author of "Freedom to Fail" published with ASCD, and has contributed articles to ILA, ASCD, and Edutopia.