Strategies for Empowering K-5 Student-Centered Learning

Step one in integrating more student-centered learning into the elementary classroom is preparation in how to ask questions. Science is a great subject to start with because “science is all about inquiry,” says John McCarthy, a teacher and consultant to K-college educators. “I want to teach students how to have conversations as scientists, not like scientists. I tell them that they are scientists and that we’re going to do everything in our class as scientists.”

Giving Students Inquiry Tools

The value of questions is particularly relevant for science, where young students’ natural inclination to explore can be harnessed to foster fruitful discussions among students. “We don’t have to lecture,” McCarthy says. “We can give direction and let students share ideas while we actively teach and coach.” For intermediate grades, he recommends an approach known as “Talk Moves”, in which teachers instruct students on how to ask good questions, participate in the discussion in a respectful and substantive way, and incorporate methods that get all members of the class involved.

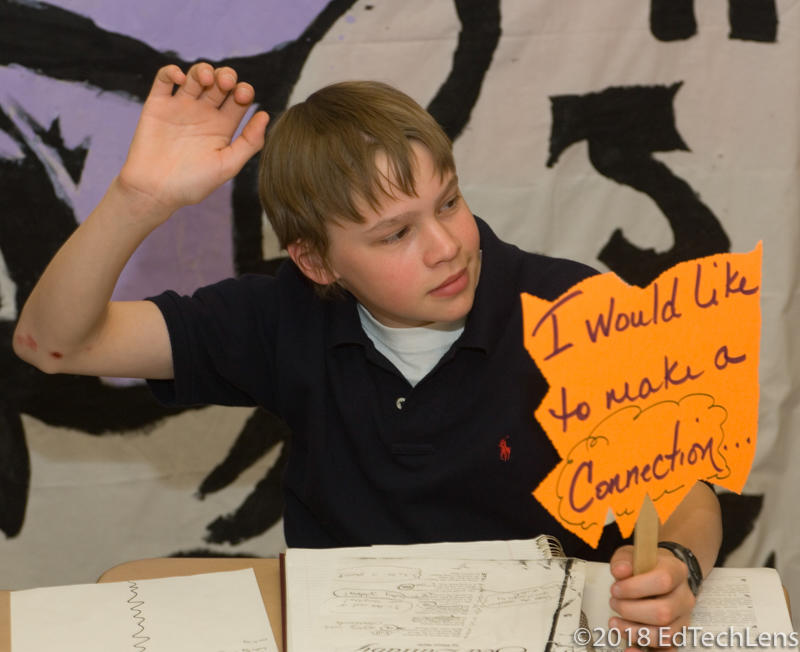

One aspect of Talk Moves is the use of starter stems for conversations, which vary depending on the situation. For example, in a discussion, a student may feel that another has said something incorrect or in some way “off,” but rather than saying this student is wrong, she uses the stem, ‘I respectfully disagree…’ and follows it with the reason she thinks there’s an error.

Learning How to Offer Productive Feedback

Another thing good scientists do is use language for respectful critique. Even very young children can understand and get into the habit of using the word “critique” as part of developing a scientific attitude.

McCarthy explains to his students the difference between “warm,” or positive feedback, and “cool” feedback and instructs them to always start with warm feedback. “We want to look at how someone’s work could be better and a big part of that is pointing out what they’re doing well,” he says. The starter stem “I like” precedes warm feedback, while the stem “I want” introduces cool feedback.

“Students can be really uncomfortable with the word ‘critique,’” he says, “and I even thought about not using it at all, but decided instead that we should embrace it and understand its value. Valuable critique is specific, constructive and kind – but not ‘fluffy.’ We keep it from being fluffy by learning how to say, not just, ‘I really like your science report,’ but offering specifics, as in ‘I liked the way your experiment tested the changes in water levels.’”

Students can learn how to give positive feedback as they suggest changes in each other’s work. They can critique by using the stem, “I wonder.” For example, “I wonder if the conclusion agrees with your hypothesis.” This way, students have a template for offering an idea even when they’re not certain of its validity.

Critique and Discussion for Younger Students

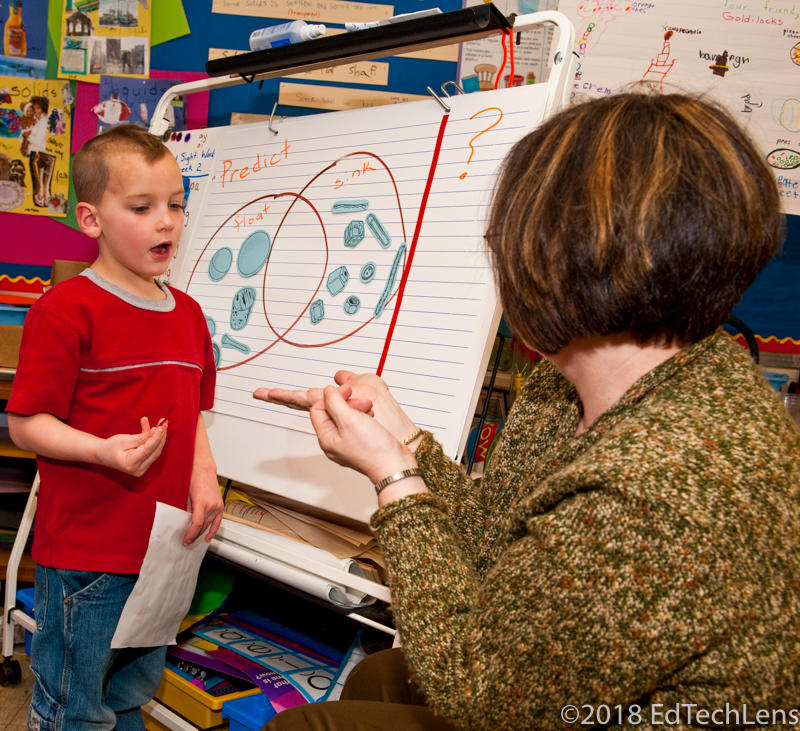

Writing skill levels can range widely in kindergarten through third grade, but McCarthy recommends guiding students through the use of constructive critique here as well. “Even if they can’t write about a subject, they can draw it, talk about it and explain it. So to me it might look unintelligible, but if they talk about it, using vocabulary and details, and explain it, then they’re making the connections.”

He describes another method that’s effective for helping younger students learn how to listen actively and participate through constructive and accountable talk. Using a fishbowl activity, students sit in concentric circles. The teacher facilitates while the inner circle of students is actively engaged in the conversation and those in the outer circle observe. Students in the outer circle are assigned a supporting role for one student in the inner circle.

McCarthy points out how helpful this can be for a team that’s struggling, as the outer circle serves as a kind of lifeline and backs up students in the inner circle with guidance. “The outer circle is taking notes and passing questions and answers to their inner circle student, so that student who’s struggling for something to say now has a small group backing her up with questions to ask. She has ‘thought partners.’ What you don’t want is the outer circle just watching and taking notes because they’ll start to tune out.”

A Strategy for Enhancing Lecture Time

The traditional approach of teachers presenting from the front of the room while students sit and listen is reduced, but not eliminated in the student-centered classroom. McCarthy says that teachers sometimes misinterpret his message. “They think I’m saying ‘lecture is bad,’ but that’s not the case. It’s a useful tool, but it also shouldn’t be the primary tool. The challenge with a lecture is that it’s usually the lecturer who’s the most engaged. Even for adults it’s hard to sit and listen to someone present information for more than ten minutes.”

Teach Reflection

McCarthy also recommends the technique of reflection as a way to make the time teachers spend presenting more engaging and productive for their students. He advises asking plenty of questions and then extending the pause allowed for students to formulate an answer. “We all underestimate the power of silence in learning – and may forget that students need time to process what they know and to make sense of what they do not understand. Allowing 30 seconds to two minutes for them to respond to a question honors the work being asked of students.”

Students do need some prep on this before instituting it in the classroom. McCarthy recommends coaching students on the value and practice of reflection. “Educators and students may appear to be uncomfortable with silence, hence the typical one-second pause time. Silence may be equated with nothing happening. In reality, when students are provided with structured ways to practice thinking and specific directions about what to accomplish within the silent time, they can become more productive during reflection,” he says. McCarthy explains techniques for working these pauses into a lecture on Edutopia.org.

The Key to a Successful Student-Led Classroom

When students and teachers are having trouble getting students to take more of a lead role in their education, what’s usually missing is the ability to ask good questions. “If someone doesn’t understand how to do inquiry, it can feel very frustrating,” McCarthy says. Fortunately there’s no shortage of strategies for helping students learn how to dialog, reflect and offer feedback, all of which are important skills for life-long learning and success in the modern world.

“Ultimately, curriculum coverage does not equal student learning. We want kids to learn more than how to ‘do school.’ If we just go by test scores, it can seem like kids don’t need any help, but what teachers are recognizing is that these kids are having less success when they get to college and career…so the question becomes, ‘How do we give them a better edge?’ and ‘How do we teach them 21st century skills in an effective manner?’” By taking advantage of the opportunities science exploration offers for students developing inquiry skills and critiquing abilities, teachers can make an important contribution to their students’ future success.

Want to learn more ways to foster a student led classroom? Read “Replacing Teacher Presentation with Student Motion“ on the EdTechLens blog. You may also find a previous EdTechLens post on “How to Engage Students with Well-Designed Questions” helpful.

About John McCarthy: The author of So All Can Learn: A Practical Guide to Differentiation, John McCarthy advocates for student voice and agency, working with schools across the United States and around the world on innovative practices, including Differentiation, College & Career Readiness Skills (aka 21st Century Skills), Authentic Learning Experiences, and Project-Based Learning. He has taught English and Social Studies in high schools in communities that were rural, urban, suburban, high poverty and high affluence, and spent years coaching in elementary to high schools. He shares his wide ranging teaching and coaching experience through his consulting practice, and is an adjunct professor at Madonna University. Learn more about John on his website.